Sheffield Daily Telegraph – Tuesday 03 April 1923

Poet’s Love Romance.

Montgomery’s Life at Wath- on-Dearne.

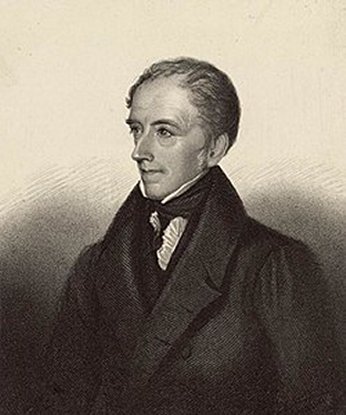

Picture from Wikipedia

Some little, time ago an engagement took me to Wath-upon-Dearne, a village once known as the `’Queen of Villages, but which to-day, owing to the beauty-destroying collieries, cannot possibly claim that distinction.

Some little, time ago an engagement took me to Wath-upon-Dearne, a village once known as the `’Queen of Villages, but which to-day, owing to the beauty-destroying collieries, cannot possibly claim that distinction.

Long ago I read with more than ordinary interest-of James Montgomery’s connection with Wath in his youth, more than 130 years since. Wishful to know if any memories of the poet still remained in the village, I found on inquiry that the house in which as a lad he had served behind the counter was still in existence.

In the High Street is a solid grey stone structure with a gabled front bearing the name “Montgomery House,” of which is friend has sent me an old photograph, here reproduced, showing the house pretty much as it was in Montgomery’s time. The original window in front had been replaced by a modern one, and for some time the premises had been used as a Bank.

Both Montgomery’s parents were Moravian missionaries, and the boy was sent to a Moravian School at Fulneck, where, strange to say, he had the character of being daring, wayward, and somewhat neglectful of his studies. On leaving the school he was placed by his guardians as shop-boy to a baker at Mirfield in the hope that his ambitions day-dreams might be dissipated.

Whilst here he varied his shop duties by the composition of poems, and after a stay of eight months, when sixteen, he ran away with a bundle of poems and 3s. 6d. in his pocket. After wandering to Doncaster, Rotherham, Wentworth, and other places, he eventually found his way to Wath, where he became assistant to a Mr. Hunt, who occupied the building already named, whose shop was stocked with flour, groceries, wearing apparel, shoes, and other goods pertaining to the trade of a general dealer. During this stay here he found a friend in a Mr. Brameld, who kept a small stationer’s shop in the neighbouring village of Swinton.

At the end of a year young Montgomery went to London with a parcel of his poems in search of fame and fortune, which, however, did not, meet him. For a time he found congenial employment with a bookseller in Paternoster Row, where he sought to cultivate his poetic gifts. After a series of disappointments, he returned, sadder and wiser, to his old master at Wath.

Diligent in business, the lad was a regular attendant at Wath Church with the family of his master, who appears to have shown him much kindness. Montgomery has given us an interesting account of a visit made to Wath more than fifty years after leaving his old place. After picturing the “wild roses courted by troops of honeysuckles.” and “the good houses intermingled with orchards in the rich valley of the Dearne” at the time of his residence, he says: “There was not one shabby house, nor hardly an indigent family.” On reaching the old stone building he exclaimed, “This was our house, the second window over the floor being my bedroom.”

Going into the Church he pointed out the pew where he used to sit with his old master and mistress. The churchyard was the scene of Montgomery’s “Vigil of St. Mark,” a descriptive poem of 38 verses relating, to a village legend. Some lines in this poem seem to point to his love romance.

Returning from their evening walk,

On yonder ancient stile,

In sweet, romantic fender talk,

Two lovers paused awhile.

The churchyard is-described as :

That, silent, solemn, simple spot,

The mouldering realm of peace,

Where human passions are forgot.

Where human follies cease.

During Montgomery’s early years at Wath began his courtship, which ended in another disappointment, one far more bitter than any he had hitherto experienced. Not far from the village was Swaithe Hall, an old-fashioned house, which from time to time he visited. Here dwelt a Mr. Turner, between one of whose daughters and Montgomery a love attachment appears to have sprung up. In 1792, when twenty years old, Montgomery, in reply to an advertisement in the ” Sheffield Register,” became a clerk in the office of Mr. Gales, the publisher of that paper, an event which changed the whole current of his life. I have somewhere read that he was accustomed to walk from Sheffield to Wath, nearly twelve miles, and it is not difficult to surmise the object of his journey. He acted as groomsman to the son of his old master, who had married Sarah Turner, and the local tradition is that he was paying his addresses to her sister, Hannah, who became the subject of one of his poems, and which tells its own tale.

This, found in a volume of his poems collected by himself, opens thus:—

At young sixteen my roving heart

Was pierced by love’s delightful dart;

Keen transport throbb’d through every vein,

I never felt so sweet a pain

Love, however, did not run smooth, but the storm blew over, and the Sea of Youth and Pleasure smiled.” One May morning, as with eager hopes he wended his way to Hannah’s cottage, bright visions of the future rose before him. He saw the village steeple, and heard the bells “sweet and clear.” All was gay, and then the unexpected happened, as given in the poet’s own words:—

” I met a wedding—stepped aside

It pass’d—my Hannah was the bride.”

After which follow the pathetic words:-

“There is a grief that cannot feel.

It leaves a wound that will not heal.”

The poem on “Hannah” was written in 1801, not very long after the catastrophe. Montgomery’s heart, as he tells us, “grew cold,” and he evidently resolved to take no more risks, for he remained a bachelor up to the day of his death. We are told, that in after life he carefully avoided referring to this tragic episode.

Montgomery’s last visit to Wath, when he was an old man, was in company with the Rev. (afterward’s Doctor) John Pye Smith, who was to preach in the village. Upon his remarking that on a previous visit long before he had been groomsman to Mr. Joshua Hunt, a friend asked if Hannah, the sister of the bride, was present on the occasion, to which Montgomery replied: Yes, she was: and I believe she was also married at Wath ; but I assure you I was not at her wedding.”

On his calling upon Mr. Johnson, a wine merchant, whose descendants are still worthily represented in the village, Mr. Johnson said to him : “Mr. Montgomery, I think you have never been married ; I have only this very day been talking to my wife about the verses you wrote upon Hannah Turner!” ” This,” says John Holland, “was like catching a butterfly with a pair of blacksmith’s tongs,” and the subject of conversation at once reverted to another topic. Such is the story of Montgomery’s love romance, of which few indeed would suspect that the poet and hymn-writer had been the subject. –